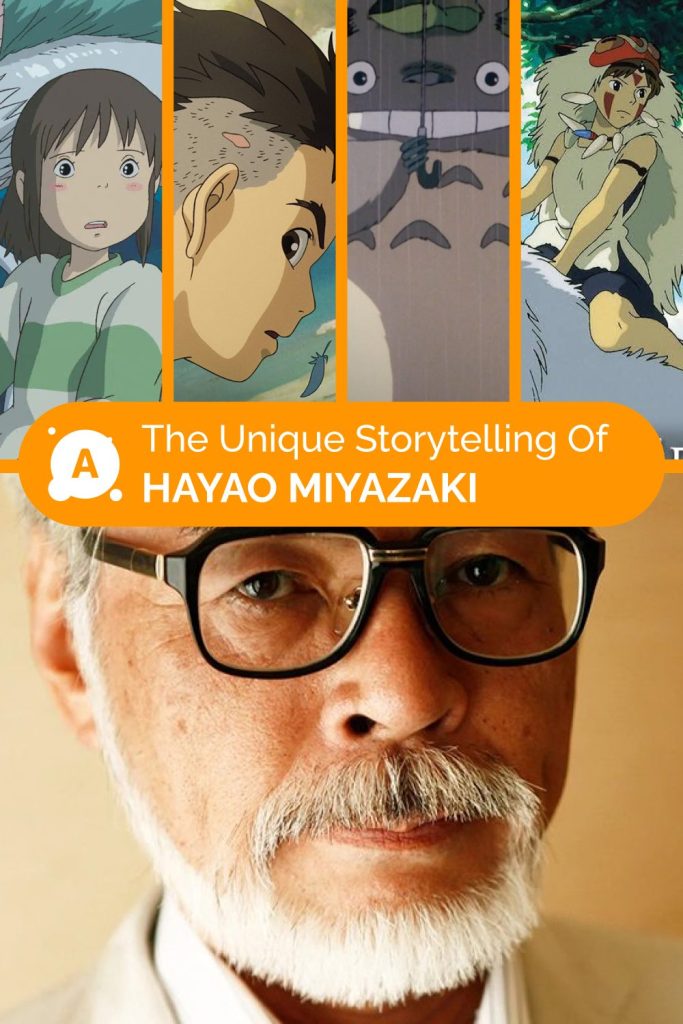

How Hayao Miyazaki Came to Be

Ten years later, a new full-length animated film by Hayao Miyazaki, “The Boy and the heron” (Kimitachi wa Dou Ikiru ka), was released in theaters. To create this project, the director was inspired by his favorite novel of the same name by Yasunari Kawabata, which centers around 15-year-old schoolboy Koporu, who experiences the death of his father. We decided to discuss the peculiarities of the style of the Oscar-winning director and his best works.

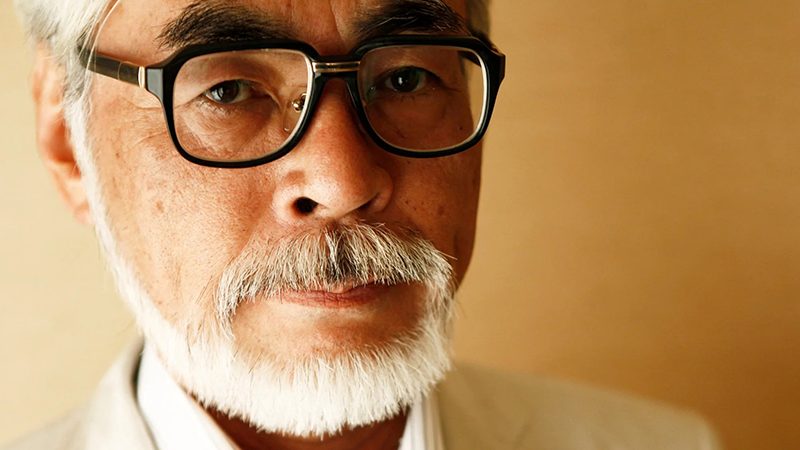

From Childhood

Hayao Miyazaki loved to draw from his childhood and dreamed of becoming a manga artist, inspired by the works of Soji Yamakawa (“Isamu – The Boy from the Desert”) and Osamu Tezuka (“New Treasure Island,” “Apollo’s Song”). The latter, like Miyazaki, made a significant contribution to the formation of Japanese animation. It was the works of Osamu Tezuka that caused Miyazaki to doubt his early works – they were often compared, so the future animator began searching for his own unique style.

The director’s style was influenced not only by manga artists: at the age of seventeen, Miyazaki went to the cinema, where he saw the animated film “The Legend of the White Snake” (Hakujaden, 1958). The film impressed him so much that Hayao immediately realized he wanted to become an animator. “The Legend” was the first Japanese color animated film that made a big impression not only on the future director, but also on the whole country. Miyazaki was thrilled by the image of a strong female protagonist, which would influence the characters of his future works: from Sheeta in “Laputa: Castle in the Sky” to San in “Princess Mononoke.”

His Dream Became Bigger than Him Alone

Hayao realized his dream and got a job as an in-betweener at the Toei Doga studio. But the difficult working conditions almost made Miyazaki give up his childhood dream and start searching for himself in another profession (even before the creation of the Ghibli studio). But fate intervened: in 1964, the future director attended a screening of the animated film “The Snow Queen” (1957) by Lev Atamanov, which was organized by the company’s union. Atamanov’s work forever changed Miyazaki’s perception of animation. Later, a poster of the film would appear in the Ghibli studio museum with the inscription: “My destiny and my favorite film.”

“If I hadn’t seen ‘The Snow Queen’ during the screening organized by the company’s union,” Miyazaki wrote, “I sincerely doubt that I would have continued working as an animator.”

Miyazaki’s Animation

In his works, Miyazaki tried to depart as much as possible from the style of Disney (although he adored Atamanov’s film, which he was inspired by). The difference from his American counterparts is radical: Hayao’s works have a richer visual component and a completely different dynamics. Why is that? The thing is, when the director was just starting his career, Japanese animation had a relatively low budget. Americans used twenty four frames per second, each drawn by hand – which took quite a long time. Japanese animators, to save money, used only twelve frames, so the process was much faster. Due to the smaller number of frames, it was not possible to animate faces subtly, and the figures were less realistic. This is where Miyazaki showed ingenuity. For example, in “Spirited Away,” when Chihiro feels disgusted at the appearance of the “Stink Spirit,” her hair stands on end and fluffs up. It’s a bright detail that catches the eye, which appeared repeatedly in the director’s works and became his signature move.

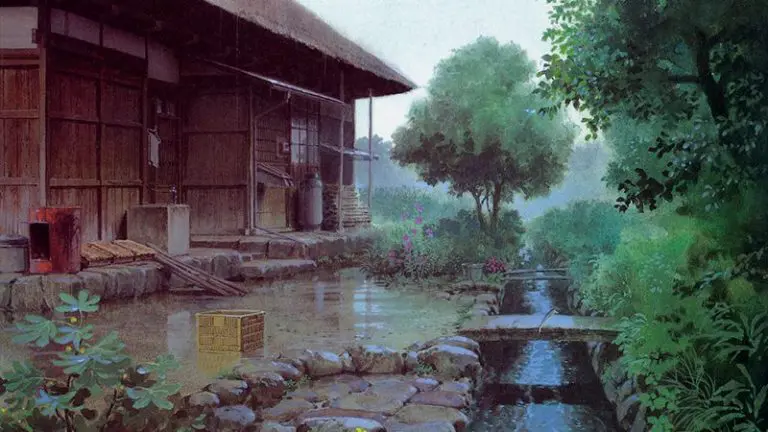

The believability of the scenes was also achieved through the backgrounds. Hayao’s landscapes are striking: emerald fields under a blue sky with soft white clouds, against which Howl’s Moving Castle strolls; a tram running straight on water in “Spirited Away.” It’s something that stays with you forever!

The Anxiety of Growing Up

A special place in Miyazaki’s works is occupied by the theme of growing up. Saying goodbye to childhood is accompanied by fears and anxieties that the characters must overcome in order to mature.

Chihiro from “Spirited Away” struggles with the move to a new city and saying goodbye to classmates. But ahead lie much more traumatic trials: the family takes a wrong turn and ends up in an abandoned town, where the parents decide to have a meal despite the absence of staff. In reality, they eat offerings meant for spirits, and as punishment, the witch Yubaba turns them into pigs. Chihiro is left alone. She has to cope with horror (spirits are everywhere) and grief (loss of guardians), trying to navigate through the new circumstances.

The biggest fear of a child is losing their parents. It is this loss that pushes the girl to overcome her fears and grow up. Chihiro seeks help from the spider-like grandfather Kamaji, negotiates with the powerful and evil witch Yubaba for a job, and engages in hard work in the public baths. The child and the adult switch places: now the girl must stand up for her guardians and show leadership qualities, perseverance, and courage.

Despite Chihiro’s decisive actions, the weight of what is happening is felt: Miyazaki conveys the child’s melancholy through images and surroundings. When the girl is on the balcony eating an “An-pan” bun with her neighbor and barely holding back tears, an endless dark ocean stretches ahead, merging with the blue sky—a symbol of longing. And the lights ahead represent hope.

Feelings of Loneliness

Another vivid character is No-Face. The dark spirit with a white mask, whom the girl lets into the bathhouse, symbolizes her fear of abandonment and loneliness. No-Face’s emptiness reflects the girl’s internal crisis, and his insatiability (for money, food, and even guests) represents her need to “feed” her loneliness, to fill it. No-Face takes Chihiro for his own: she understands him and lets him into the building, but their paths diverge when the girl realizes the spirit’s insatiable nature, refuses the gold he offers, and finds a way to calm No-Face down. In doing so, she rejects the fear of loneliness and gains an ally.

The next step in growing up is overcoming fears and finding love by returning Yubaba’s seal and Haku’s identity (who has also lost himself and is searching). Overcoming fears allows Chihiro to mature not so much externally as internally: when entering the mystical town, the girl tightly held her mother’s hand and hid behind her, but when leaving, she crosses the metaphorical bridge from childhood to adulthood independently. And most importantly—she does not look back.

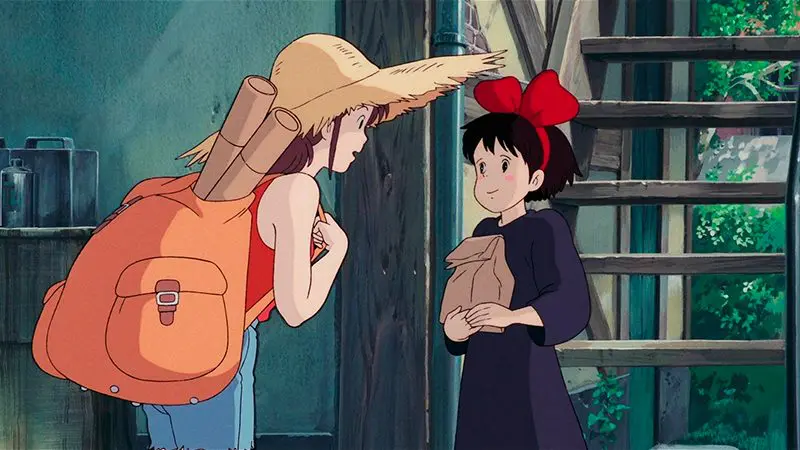

Chihiro is not the only one facing similar problems: Sita from “Castle in the Sky” and Kiki from “Kiki’s Delivery Service” also go through difficulties in making adult decisions and overcoming crises. Sita loses her parents early and tries to save the flying island alone, while Kiki starts her independent life and struggles with apathy and crisis as a teenager.

The Joy of Aging

What about aging? Here, Miyazaki’s attitude changes dramatically. The director presents old age not as something terrible—everything hurts, memory is not the same, and beauty has disappeared. He ridicules these problems.

For example, Sophie from “Howl’s Moving Castle,” unexpectedly transformed into an old woman, experiences all the charms of old age. Her back creaks, she can’t straighten up, and what about her face? But the granny actively wields a broom in Howl’s castle, falls in love, and makes fun of what’s happening (who would react so calmly to a curse in her place?). Outside, Sophie is an old woman, inside—a young girl. And it’s not about the curse; that’s how the aging process itself is seen by the director:

“Does a person change at eighteen or sixty?—says Hayao. —I believe that a person remains the same.”

of life and enjoys every little thing

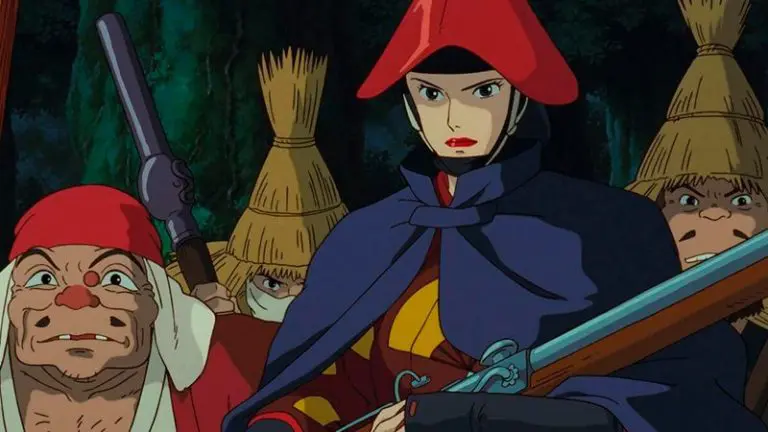

In old age, there is room for love, like Sophie’s, sincere interest in one’s work, like Uncle Pom’s cave exploration, and strange adventures like those of Dora the pirate from “Castle in the Sky”… Age is just a number. You can enjoy life anytime. After turning into an old woman, Sophie finds meaning in life and rejoices in every little thing.

Mysticism and Japanese Mythology

The works of Japanese animators are inseparable from the mythology of the country — spirits are too closely connected with all spheres of life. Miyazaki’s creativity is imbued with Shinto motifs, worshiping the Kami deities, which inhabit everything that surrounds humans (nature, natural phenomena).

Spirited Away

At the mention of the word “spirits,” “Spirited Away” immediately comes to mind. Chihiro experiences “Kamikakushi” — the abduction of a person by spirits and his return to people only after several years (when the girl exits the otherworldly world, the road is overgrown, and the car is covered with leaves and a layer of dust). Kami can not only abduct a person but also take his name, as happened to Chihiro and Haku when Yubaba hired them. A person can enter the otherworldly world only if he thirsts to escape from reality, but it is much harder to return.

Chihiro works in public baths visited by spirits. Here is the River Spirit, who appears in the building so dirty that Yubaba mistakes him for a spirit of garbage; and the green-headed Daruma spirit, which brings luck and fulfills wishes; and Kintaro — Yubaba’s son and a hero of Japanese legends, possessing superhuman strength; and paper birds Shikigami — evil spirits summoned by a powerful sorcerer.

The director spoke about it like this:

“In the times of my grandparents, it was believed that Kami existed everywhere: in trees, rivers, insects, wells. My generation doesn’t believe in this, but I like the idea that we should cherish all existence because spirits may dwell in it. Everything has life.”

My Neighbor Totoro

In the anime “My Neighbor Totoro,” Satsuki searches for her missing sister Mei and accidentally encounters a tree with a Shinto shrine of the forest spirit Totoro. The tree in which it resides is adorned with Shimenawa ropes, marking the sacred space. The creature helps the girl reach her sister. Mei is found on a country road next to small Jizo statues — protectors of children. Shinto relics are invisibly present in all of Hayao’s works.

However, debates about the essence of Totoro continue to this day. On the one hand, the raccoon-like spirit dwells in the shrine. On the other hand, Satsuki calls him “Obake,” which translates as “ghost” or “monster,” and Miyazaki himself insisted that Totoro is a forest creature that feeds on acorns.

But the clear spirit of the forest appeared not in “Totoro” but in the anime “Princess Mononoke.” Shishigami resembles a deer with plant-like antlers and a human face. He protects the Cedar Forest, and he is also the spirit of life and death (he heals Ashitaka from a gunshot wound). In Japanese mythology, such a spirit is called “Yatsukamidzuomitsu-no” and is depicted as a deer with a tree on its head — the force shaping the planet.

Princess Mononoke

Another memorable spirit from “Princess Mononoke” is Kodama. These are small, snow-white tree spirits with big black eyes. Their presence is a sign that the forest is healthy. After Lady Eboshi cuts off the head of the Forest Spirit, the Kodama die along with the forest. As the land heals, the spirits gradually return, reflecting the rebirth of life.

Interaction between Humans and Nature

From his earliest works, Miyazaki speaks about the destructive interaction between nature and humans.

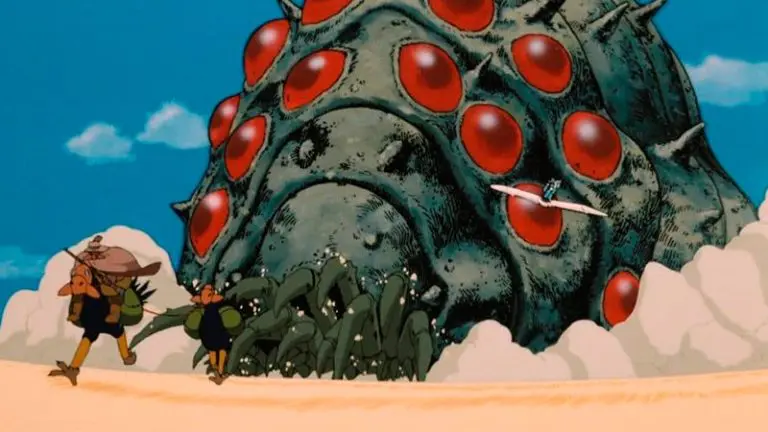

In “Laputa: Castle in the Sky,” the characters land on an island and accidentally cover a songbird’s nest with their flying vehicle. The robot that watches over the garden and animals in Laputa carefully frees the nest so the birds can return to their offspring. The director emphasizes the characters’ concern for the fate of the chicks and the robot’s careful treatment of flora and fauna. Sheeta and Pazu are deeply disturbed by the invasion into the mystical nature of the island. People driven by greed, on the other hand, pay no attention to it, destroying and plundering. In the end, the island is freed from technology, leaving only its core — the tree disappears into the clouds. Miyazaki seems to say: if humans don’t know how to treat nature with care, then there is no place for them in it.

His heart remains – nature

In “My Neighbor Totoro,” the director focuses on Japan, where humans and nature are in constant interaction: farms, villagers, mountains, cultivation of the soil. There are no instructions or didactic moments in the work, but the landscapes and atmosphere instill in the viewer a sense of loss of harmony with the surrounding world, which is a leitmotif in all of the master’s projects.

In “Princess Mononoke,” the sense of loss is even deeper; it becomes the core of the plot. Human greed, consumer culture, and the relentless drive for progress led by Lady Eboshi have destroyed the natural world, so nature is forced to fight back. Miyazaki gives voice to the silent victims of humans: the spirits of the forest and animals can finally stand up for themselves, with the help of San. The slow revival of the forest spirits at the end — a hope for humans to abandon destruction in favor of harmony and world restoration.

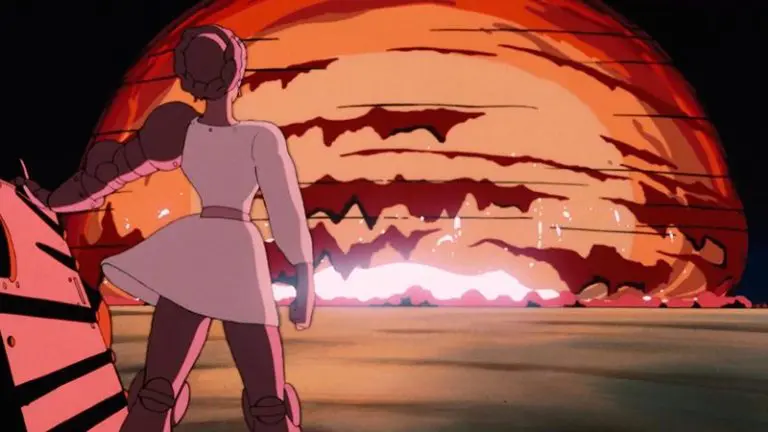

Post-apocalyptic

A similar message is found in “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.” The princess tries to protect a post-apocalyptic world filled with remnants of old civilizations. Part of humanity survived and faced the consequences of industrial wars: the soil and water are contaminated, large poisonous mushrooms grow in the forests, and mutant insects crawl around. The girl tries to save her village from giant arthropods and the consequences of the thirst for power. The anime vividly shows what human indifference to nature and the consequences of their choices lead to.

In “Spirited Away,” the spirits punish Chihiro’s parents for greed and “uncontrolled consumption,” turning them into pigs: “when people try to fill their spiritual emptiness with material goods, consuming more and more, they lose their human face.”

Hayao constantly reminds the viewer that we are merely guests in this world and must treat our home with care.

Evil is not what it seems

Only in Miyazaki’s early works were antagonists clearly defined, such as Count Cagliostro in “The Castle of Cagliostro” or Muska in “Castle in the Sky.” But in subsequent works, the lines between good and evil became less clear, and actions were not interpreted unambiguously. The director treats each of his characters with understanding and sympathy, understanding that there is always a reason behind actions, even bad ones.

For example, in “Howl’s Moving Castle,” the Witch of the Waste, who decides to curse Sophie out of jealousy for Howl, listens to the girl’s pleas and releases the young man’s heart.

In “Princess Mononoke,” Eboshi sides with humans, while San sides with the forest; their viewpoints are opposite, but each has the right to exist. The attempt to protect their own leads to the deaths of people by Eboshi’s side and the forest spirits by San’s. Thus, Miyazaki shows that conflict is not a struggle of good against evil, but a collision of viewpoints, each of which is true in its own way and therefore has the right to exist.

From Friend to Foe and vice versa

Asitaka is the intermediary between conflicting parties, witnessing how they annihilate each other. Only he realizes the truth: hatred leads to the demise of both sides. The curse placed on Asitaka’s arm is a symbol of the malice that gradually consumes a person from within until nothing is left of them. Miyazaki doesn’t allow the audience to choose sides; he shows what’s happening from Ashitaka’s perspective — neutrally. It’s from this angle that it becomes clear that the main thing in the world is the balance and harmony between humans and nature.

“The absence of a clear definition of good and evil is related to my views on the 21st century as a complex time when old norms need to be reconsidered. Stereotypes cannot be used even in children’s films,” Miyazaki explained. “Sometimes I have a pessimistic view of the world, but I want to show children a positive worldview.”

Strong Female Characters

Most of Miyazaki’s anime protagonists are girls. His works are filled with strong female characters who are not only equal to men but also surpass them in courage and determination.

“In many of my films, there are strong female characters — brave, self-sufficient, who fight for what they believe in with all their heart,” says Miyazaki. “They need a friend or ally, but never a savior. Any woman can be a hero, just like a man.”

The director often criticizes the anime industry for excessive sexualization and stereotyping of female characters. He himself presents beautiful women, but with greater respect and a touch of detachment. For example, Madame Suliman from “Howl’s Moving Castle” or Nausicaa from “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.” First and foremost, we hear their voices and see their character, and only then do we carefully examine their appearance.

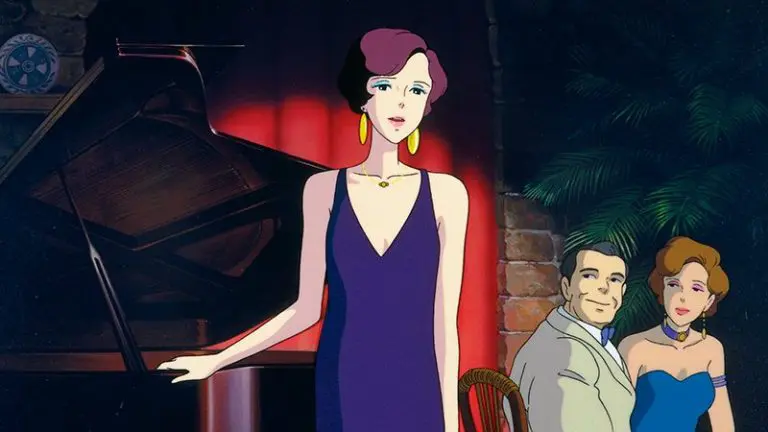

Girls in Hayao’s anime appear not as mere additions to the main character: even in minor roles, women possess vibrant personalities and steadfast goals. For example, the stern and active leader of the pirates, Dola, in “Castle in the Sky,” or the magnificent singer Gina from “Porco Rosso.”

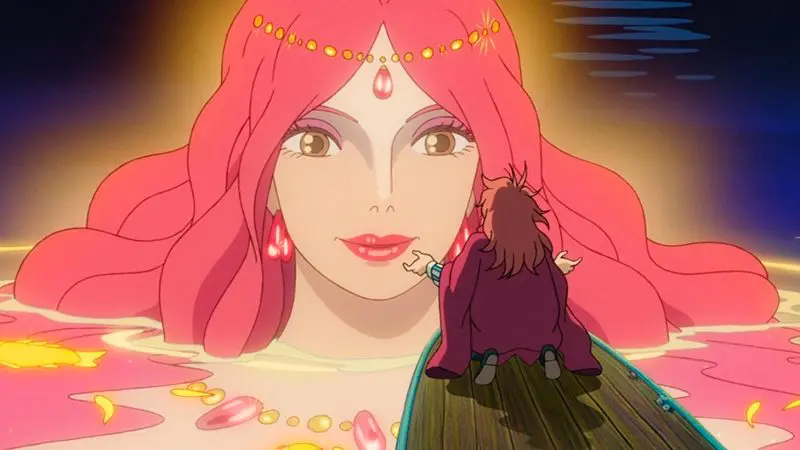

How Women are different

Women in the animator’s works change the course of the story, exert a great influence on the characters, and are capable of healing with the power of their love. This is Fio from “Porco Rosso,” who restores Porco’s human form; and Chihiro from “Spirited Away,” who returns Haku his name; and Sophie from “Howl’s Moving Castle,” who finds Howl’s heart; and San from “Princess Mononoke,” who defended the forest from humans almost single-handedly.

Even in lighter films like “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” the main female characters are determined, demonstrating professionalism in their field (like the artist Ursula or the baker Osono). And witch Kiki, losing her ability to fly, finds support not in a romantic interest but in the strong and experienced Ursula.

Love is the key to salvation

In many of Hayao’s works, love becomes the force that helps lift the most terrible curses, gain experience, and learn something. For example, in “Princess Mononoke,” after meeting Ashitaka, San tries to look at the world with eyes unclouded by hate and forgive people. Even though the heroes didn’t kiss, the love between them is real and felt without words.

In “Howl’s Moving Castle,” Sophie reconciles with the fate of a hatter, afraid to follow the call of her heart. She feared love, and her lack of self-confidence exacerbated the situation. The meeting with Howl changed not only Sophie but also the owner of the castle. Howl taught her that appearance doesn’t matter, as he loved Sophie even in the guise of an old woman, and through interacting with his environment, she gained self-confidence.

and helped overcome them

Throughout the storyline, Sophie’s appearance changes: she gradually becomes younger. This reflected her slow acceptance of herself. In turn, Howl overcomes cowardice and apathy, while Sophie, with the power of love, manages to lift the curse from him. The same happened with Chihiro: the girl saved Haku from the curse of the witch Zeniba with her sincere feelings.

and sets him free. In turn, the young man

helps the girl adapt to the world of spirits

Flights and Catastrophes

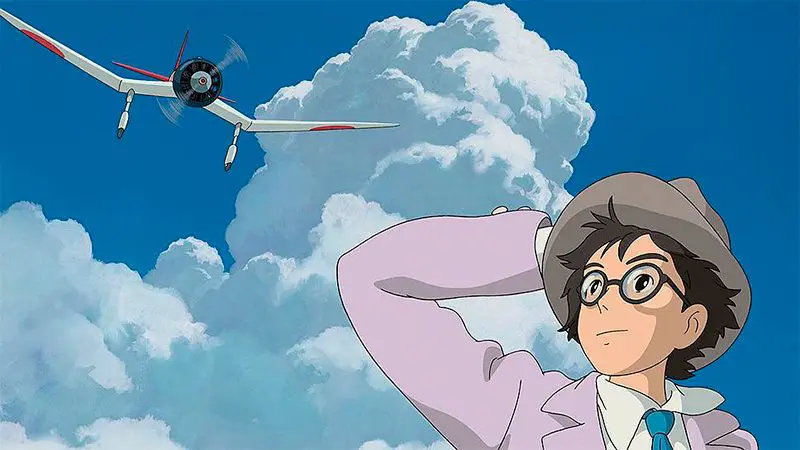

During World War II, Hayao’s father was the director of “Miyazaki Airplane” — a factory producing parts for deck fighter planes. Even in childhood, the future animator fell in love with flying machines and often made flights a central theme in his early works.

For the director, flying is a way to escape gravity and feel freedom. Liberation is felt in “Castle in the Sky” when Sheeta and Pazu soar through the clouds, and in “Spirited Away” when Chihiro, holding onto the horns of the dragon Haku, crosses the heavenly space. Even a simple gaze of the heroes at the clouds (Sheeta and Pazu emerge from a cave and look up) gives a sense of freedom and flight.

Castle through the clouds

But there is another view of the sky. In “The Wind Rises,” Jiro designed airplanes that later participated in kamikaze missions and the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Hayao does not give him an assessment but allows the viewer to independently comprehend what is happening.

When Hayao was three years old, his family, fleeing American bombings, evacuated to the city of Utsunomiya, and then to Kanuma. The events he experienced were reflected in the anime “Porco Rosso,” the action of which takes place between the First and Second World Wars. Marco Pagot is a veteran of the First World War. Disillusioned with people and life, the hero attracts a curse that transforms his human face into a pig’s.

References to Fairy Tales and Legends

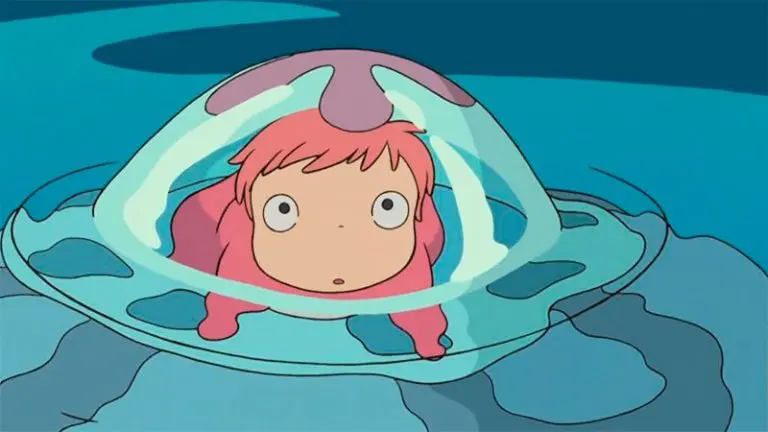

The blending of Japanese folklore with Western fairy tales endows Hayao’s works with a special magic and sensuality, childish and touching sincerity. “Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea” is a peculiar reinterpretation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid.” Brunhilde is Ariel, seeking independence from her authoritative wizard father on land. However, in Hayao’s work, her desire to break free from the ocean is not dictated by romantic interest but by friendship with the boy Sosuke, who affectionately calls her Ponyo.

“Ponyo” was influenced not only by European fairy tales but also by the 19th-century Japanese poem “The Ballad of Hojoki,” in which a golden fish becomes contaminated with human blood. Ponyo’s mother is the Japanese goddess of mercy and, at the same time, the Greek goddess of the sea, Thalassa.

Different from the Classics

In “Howl’s Moving Castle,” it’s hard not to see references to “Beauty and the Beast.” Howl is a cursed and traumatized “monster.” Sophie, like Belle, is forced to stay in the castle and gradually fall in love with its owner in order to break the spell in the end. In “Spirited Away,” echoes of “Alice in Wonderland” are evident—Chihiro, like her European predecessor, finds herself in a magical world where extraordinary and inexplicable things happen: spirits roam the streets, people transform into dragons, and an old man has spider legs. Alice finds a potion that says “Drink me” and “Eat me,” while Chihiro receives a treat-medicine.

Beloved Works For More than a Generation

Hayao Miyazaki’s works are considered some of the best in their genre for a reason. The plots do not follow conventions: strong heroines are at the center of the narrative, and the main themes are not so much about love as they are about the interaction between humans and nature, the complexities of growing up, and the joy of aging.

His characters are not good or evil, but rather alive and real. Drawing from Shinto religion in his anime, Hayao respects the traditions of his ancestors while also keeping up with the times, asserting that in old age, life is just beginning, and it’s never too late to change your life for the better.

It remains to be seen what the central theme of Miyazaki’s new animation project “How Do You Live?” will be. Meanwhile, we eagerly await it, rewatching Miyazaki’s old but beloved works!

WANT TO BEGIN YOUR ANIMATION ADVENTURE? START HERE

Sources:

https://variety.com/2023/film/news/miyazaki-hayao-final-film-how-do-you-live-secrecy-1235632765

https://animationobsessive.substack.com/p/hayao-miyazakis-favorite-film#footnote-1

https://animationobsessive.substack.com/p/hayao-miyazakis-favorite-film#footnote-1

https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/hayao_miyazaki_179317

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kami

https://intellectdiscover.com/content/journals/10.1386/fm.5.3.19_1

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0436358

Author: Arina Pyrina