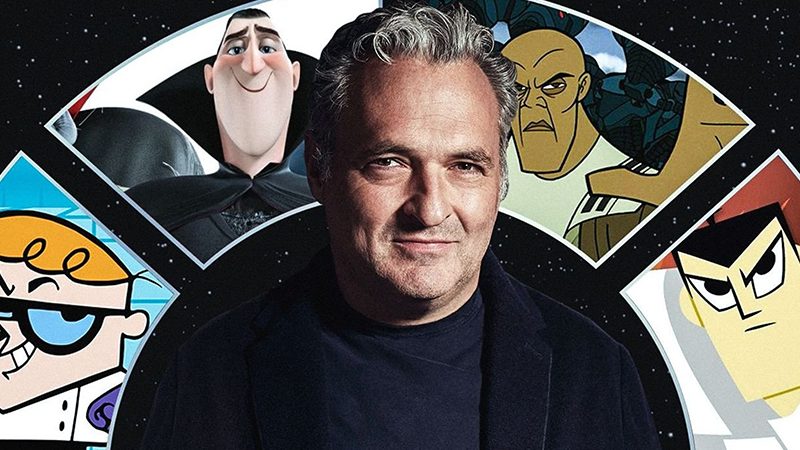

How Is Aaron Blaise?

Aaron Blaise is a renowned animator and director at Disney Studios. Blaise has worked on creating full-length animated films such as “Beauty and the Beast,” “Aladdin,” “The Lion King,” “Pocahontas,” “Mulan,” and “Brother Bear.”

In 1988, Aaron Blaise graduated from Ringling College of Art and Design. After receiving his diploma, he underwent selection for an internship at Disney Studios. Aaron was skilled at drawing but had never animated his drawings.

As a mentor, Blaise was approved by Glen Keane, who was one of the leading animators at Disney. It was Keane who taught Aaron Blaise the art of animation, which he carried through his entire creative life to this day.

Aaron Blaise’s career at Disney lasted until 2007.

Aaron Blaise: creativity today

Aaron Blaise works in a home studio, which he equipped himself. Despite his love for traditional drawing, Blaise creates animation in TVPaint software on a Wacom Cintiq Pro tablet.

One of Blaise’s recent commercial projects was the advertisement “The Bear and The Hare,” in which he served as a character designer and animator. The commercial combined traditional hand-drawn and stop-motion animation.

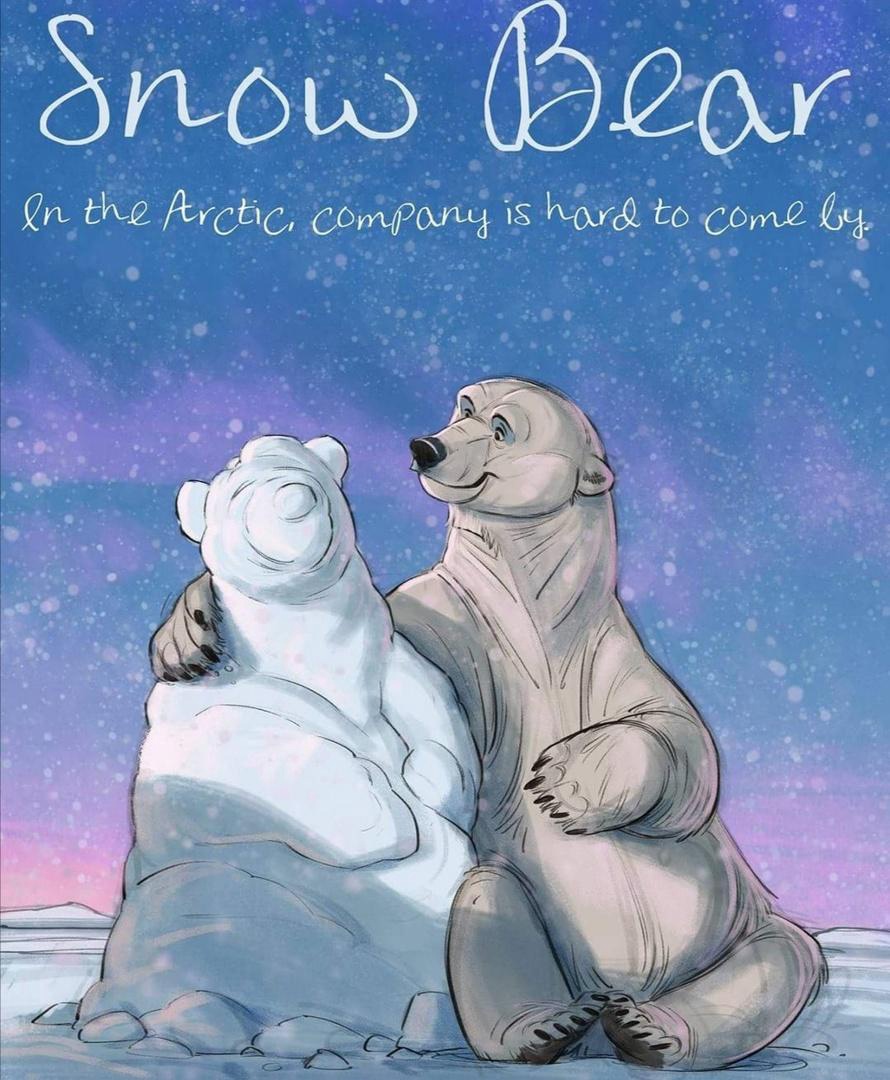

Working on this project inspired Blaise to create his own short animated film titled “Snow Bear.”

“Snow Bear”

The main idea was to draw each key frame without final processing. This way, the viewer could observe not only the characters coming to life on the screen but also see the movement of the lines used to draw the character.

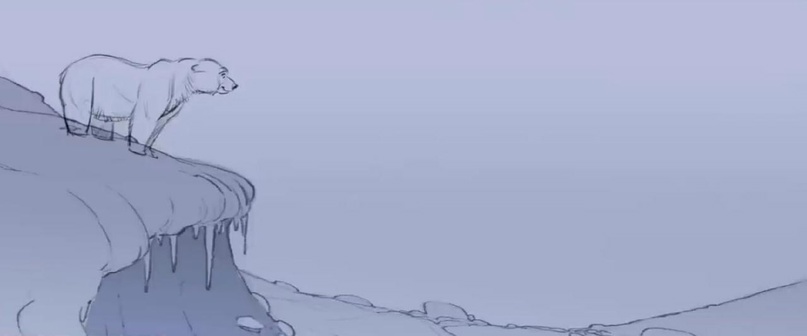

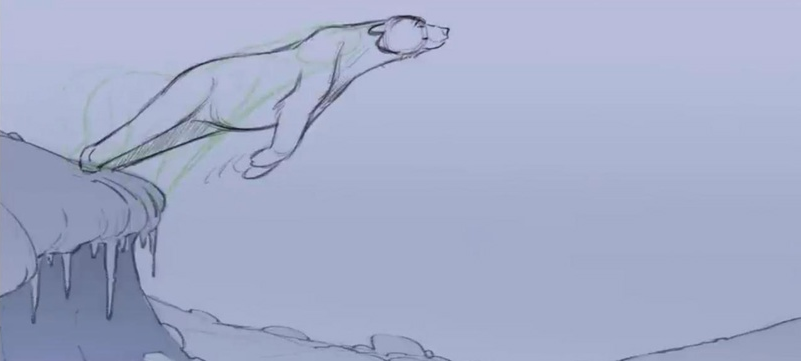

Let’s take a closer look at the leap of the polar bear.

The action takes place on a slope densely covered with snow. The animator pauses to introduce the viewer to the character.

The bear begins to walk with its right hind leg. It acts as the lead, providing the impulse for the movement of the other limbs.

When dealing with multiple characters in a scene, Blaise advises highlighting a dominant character and directing the movement of the others relative to the main action.

The same applies when movement is implied for all parts of one character’s body.

One must consider that the bear’s paws move through the snow and are hidden beneath it by several centimeters.

As it walks, the front paw must be shown on the surface and placed back under the layer of snow, indicating the weight the character exerts on it.

The movement of the left paws occurs on the same principle.

During the walk, the head moves up and down in an arc. Smooth arcs and trajectories are crucial for conveying natural movement.

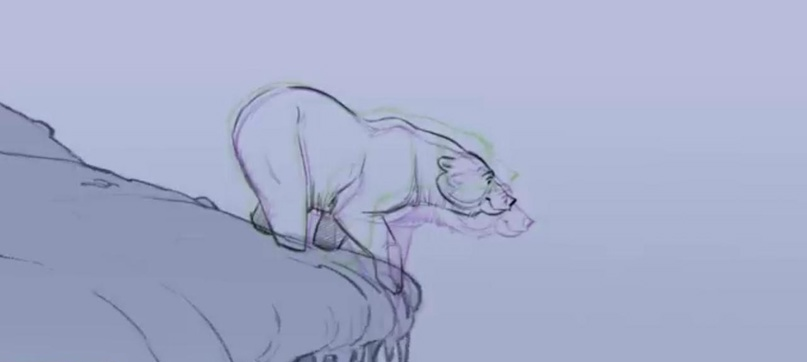

Aaron gradually prepares the bear for the jump. It will be much more dynamic and therefore will take less time than the preparation stage.

The final pose before the jump. Aaron Blaise completes all secondary actions, while maintaining a pause before the next frame.

The bear prepares to push off from the surface of the slope.

There is a shift in the center of gravity to the hips and hind legs, it crouches down and pushes off.

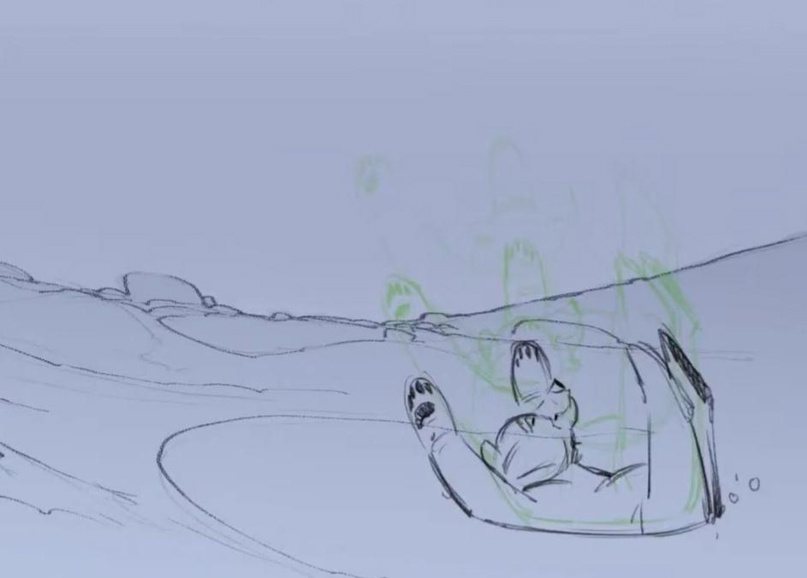

“When I animate, I notice that there’s never too much stretching, especially if the action happens quickly. You can get away with a lot more than you think,” Aaron notes.

This refers to the fact that as long as the character maintains the trajectory of movement along the specified arc, all manipulations with its shape, compression, and stretching look believable.

Let’s pay attention to how the front paws stretch. The push from the ground and the stretching occur simultaneously, while the movement of the character’s chest, paws, and head are still secondary. The neck, cheeks, ears, and the bear’s head are also subjected to stretching; the bear’s head is thrust forward, and even the nose appears more elongated.

The hind legs are stretched not entirely naturally for a living creature, but this technique allows for a sense of dynamic pose when viewing the animation as a whole. This trickery adds expressiveness to the scene.

The bear detaches from the ground and heads towards the highest point of the maneuver.

The abdomen becomes the heaviest part of the character during flight. In this pose, the animator emphasizes the shifted center of gravity, which serves as the impulse to overcome the subsequent distance.

Blaise holds the character in the highest pose to allow the viewer to capture the moment. Next comes the transition to the conclusion of the story – the bear’s fall.

The bear’s body stretches again. If in the first part of the animation, stretching served as an impulse for the jump, then in the second half of the animation, stretching is an intermediate phase before the completion of the character’s action and the entire scene as a whole.

At the moment of contact with the surface of the snow, the stretching is greatest – in this frame, the character reaches maximum falling speed.

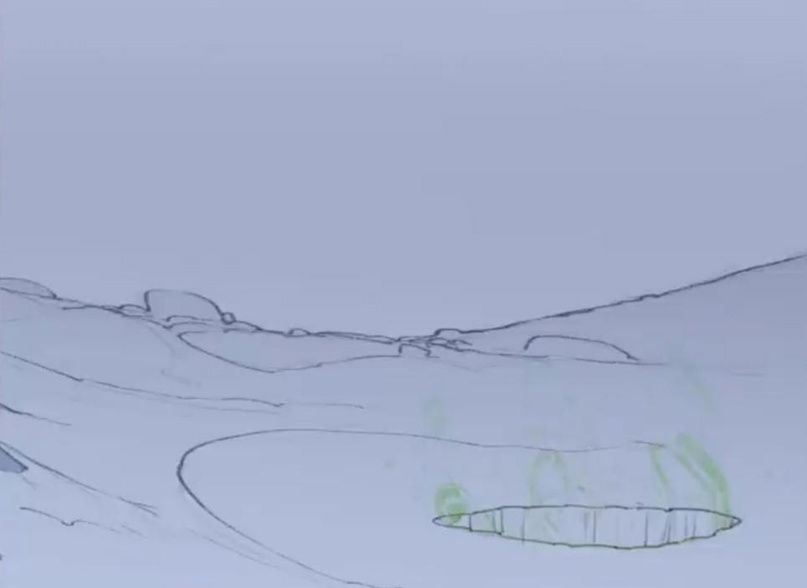

Next, the bear sinks into the drift. The story ends.

A brief pause is held for better perception by the audience of what has happened.

In the process of animating, Aaron Blaise relies not only on his knowledge of the mechanics of his character’s body but also keeps in mind the story, intentions, feelings, emotions, and character traits.

“I always perceive his enthusiasm as my own. The animation of this jolly fellow reminds me of myself at eight”.

In his work, Aaron Blaise uses the twos animation method. With twos animation, in the commonly accepted meaning of 24 frames per second, we get a new image every second frame, or 12 different pictures per second.

In addition to the above, Aaron Blaise has many useful tips that we invite you to familiarize yourself with.

Aaron Blaise’s Basic Animation Structure

Before starting the animation process, Blaise strongly recommends exploring the concept, identifying its dynamic moments, and areas where everything unfolds calmly and steadily.

The uniformity of movement among characters, objects, and background details throughout the entire work can appear quite dull and may negatively affect the perception of the scene.

But as soon as you add dynamics, such as changing the perspective, the character’s position, or the environment, shifting the horizon line or adjusting the lighting, the scene can come alive with new colors.

Blaise emphasizes that in the process of character design, their poses, or actions, it’s essential to emphasize the main elements and relegate secondary ones to the background. Avoiding a measured depiction is crucial.

In the sketch on the left, the entire composition is evenly arranged. The face is anatomically correct. The upper half of the head is the same size as the lower half. There’s nothing unusual or interesting about the character.

Now, take note of the perspective construction of the character’s facial features drawn on the right; the tilt of his head and the exaggeration of emotions.

The smile is positioned quite high, and the boy’s ear is pulled strongly toward his head, which isn’t entirely realistic, but for visual effect, it works exceptionally well.

Because the face and hair together create a larger area for perception, the viewer can better interpret the character’s emotions, as the gaze is now directed to the center of the boy’s face.

The importance of a good silhouette

Regardless of the type of visual art you plan to pursue, a good silhouette is the foundation of storytelling.

In this image, there’s nothing present except silhouettes, yet we understand who is in the illustration, what they are doing, and the story being told.

If the silhouette is poorly readable, Blaize suggests reconsidering it. Perhaps changing the perspective, slightly rotating the character, altering the positioning of body parts or objects, all to make the pose more expressive.

Expressive poses

Aaron Blaize believes that good animation doesn’t require drawing many complex elements or an endless number of frames, each filled with a unique image.

Blaize states that animation is primarily about experiencing the character’s story. And any story can be convincingly and simply told by using the most expressive poses.

Let’s see how Blaize’s theory works in the example of the Memories clip.

The scene consists of dialogue and poses, each belonging to a specific line and emotionally colored regarding what the character is trying to convey to the viewer.

• “Memories…” – these are the character’s reflections. While she utters the first phrase, the pose is fixed.

• “They warm you from the inside.” The next action demonstrates good memories. The rabbit stretches out, hugging her front paws, enjoying the warmth she managed to capture.

• “But they also tear you apart,” – the character’s last dialogue line. It makes her change the emotion from joy to sadness, reflected in the pose: now she has lowered, directed her gaze to the ground, demonstrating complete disappointment.

The entire animation consists of four poses, imbued with the heroine’s reflections. Each of them is very simple but extremely clear in demonstrating the emotions experienced.

Blaze says that the main task of an animator is to find phrases capable of fully revealing the plot. After that, select poses that reinforce these phrases, connecting them through animation.

Another technique by Blaze to make animation expressive is not just to display a character’s pose and move on to another, but to take one pose and work on individual elements within it.

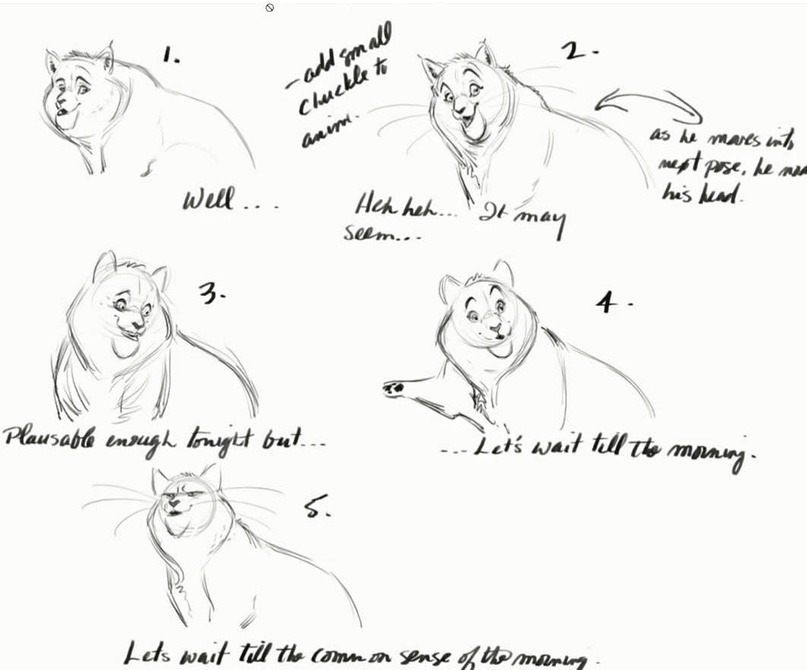

This happens in the animation of a cat.

The action is encapsulated in five expressive poses of the character, and the dialogue is fully revealed within each of them. Aaron Blaze draws the viewer’s attention to how the cat nods its head during the transition from the second to the third pose, how its emotions change, and how its neck stretches at the end of the animation.

Expressive poses, according to Blaze’s opinion, can not only affirm the character’s speech, but also tell a story on their own.

Motion Overwhelm in Animation

During the animation process, it’s essential to consider, says Blaze, that one action causes the nearest part of the body, clothing, hair, or any details of the character to move. Moreover, all elements move asynchronously and depend on their own weight, material, and external influences.

For clarity, Blaze suggests comparing the animations of two points:

on the first one – the point moves at its own speed and along a predetermined path.

But once a rope is attached to it, entirely different movements appear, not coinciding in timing and trajectory.

Aaron Blaze’s advice: think about the physics of the object you want to animate and its impact on the nearest parts of the character or objects. This approach will strengthen the character’s position in the eyes of the viewer, making it more natural and understandable.

Contrast

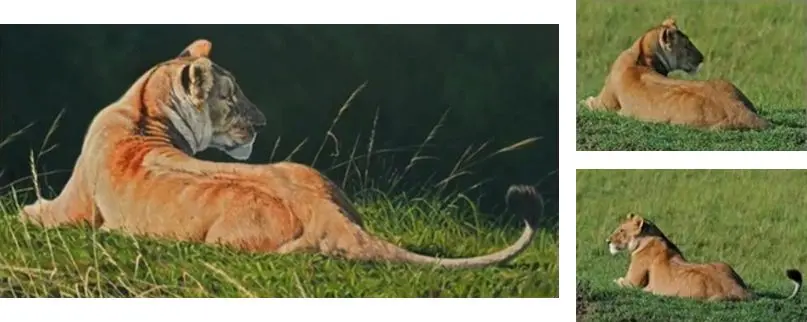

If we look at the central and rear parts of the lion, we will notice that the background and the body blending in this area are quite light, with almost no details. But as we shift our gaze to the head, we will find a darkening background, illuminated muzzle, and more elaborated details. When considering the image as a whole, it’s the lion’s head that attracts our attention.

Aaron Blaze advises infusing the work with contrast of light and shadow, delineating levels of saturation with details in different parts of the character, and making accents.

Using photographs as references

We use photo and video references, compile mood boards, and shoot performances on camera. But let me point out that misunderstanding how to use references correctly can reduce your work to mere copying.

Aaron says that references are meant for gathering information, but they should not dictate what we do.

You can gather references on the topic of your interest and analyze them. Highlight successful angles, lighting, the position of the character’s body, or the arrangement of objects and use them in developing your idea.

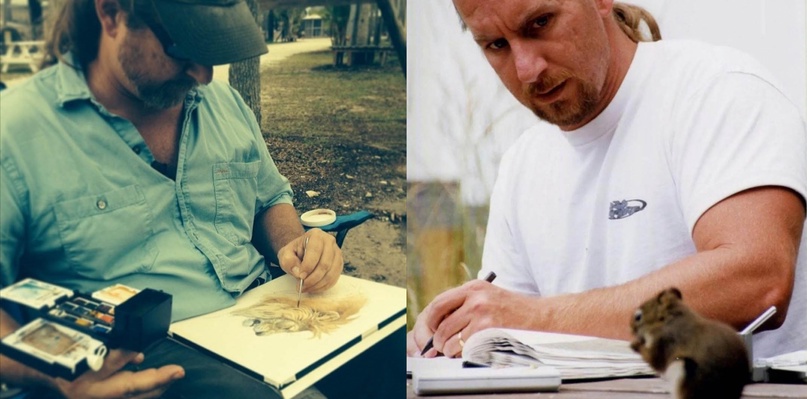

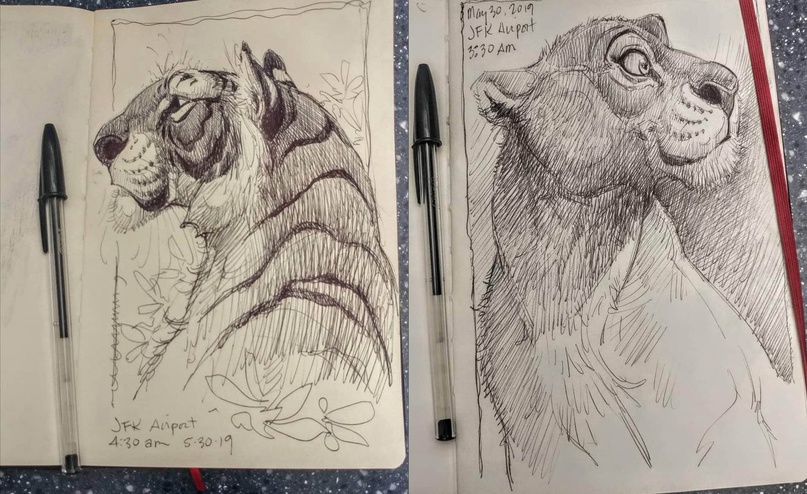

Drawing from life

Blaze has been drawing for over 40 years, and all these years he has been working on improving his skills, constantly experimenting with materials and techniques.

Blaze talks about the need to develop a habit of carrying a sketchbook and pencil with you for daily practice, sketching anything that interests you. Spend as much time on this as needed.

Draw from life. As a last resort, use videos as references. If you want to draw animals, start with your cat, the animator advises.

What to include in your portfolio

Employers want to see what you can really do at a high level in job interviews.

Aaron Blaze insists that all skills should be showcased in the portfolio first. These should be the best works, preferably in one style or direction of creativity.

“It’s better to show a few good works than a large number of mediocre ones. Good drawing, good figure, good animal drawings, color, good design, versatility – these are all things we want to see in your visual development portfolio.”

The Art of Aaron Blaise

Together with a team of artists, Aaron Blaze has been working for many years on creating educational content in the field of art and sharing his developments on his personal website.

Conclusion

Aaron Blaze, a talented artist, animator, and director, has dedicated much of his life to the visual arts, working every day to elevate his mastery. Thanks to his love and dedication to creativity, many beautiful works have come to light.

Want to become just as good an Animator as Aaron Blaze? Start taking our couses today!

Author: Maria Beskorovaynaya