What are the 12 Principles of Animation?

In 1981, animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston published “Disney Animation, The Illusion of Life”, where they first revealed the inner workings of Disney Studios. One of the main secrets revealed were the 12 principles of animation that Disney had developed and used since the 1930s.

The 12 principles are still relevant and universal for all kinds of animation, whether 2D, 3D or stop-motion. Our «Traditional 2D Animation» teachers have prepared clear examples for each of the basic principles. Use them and your animation will look convincing and attractive.

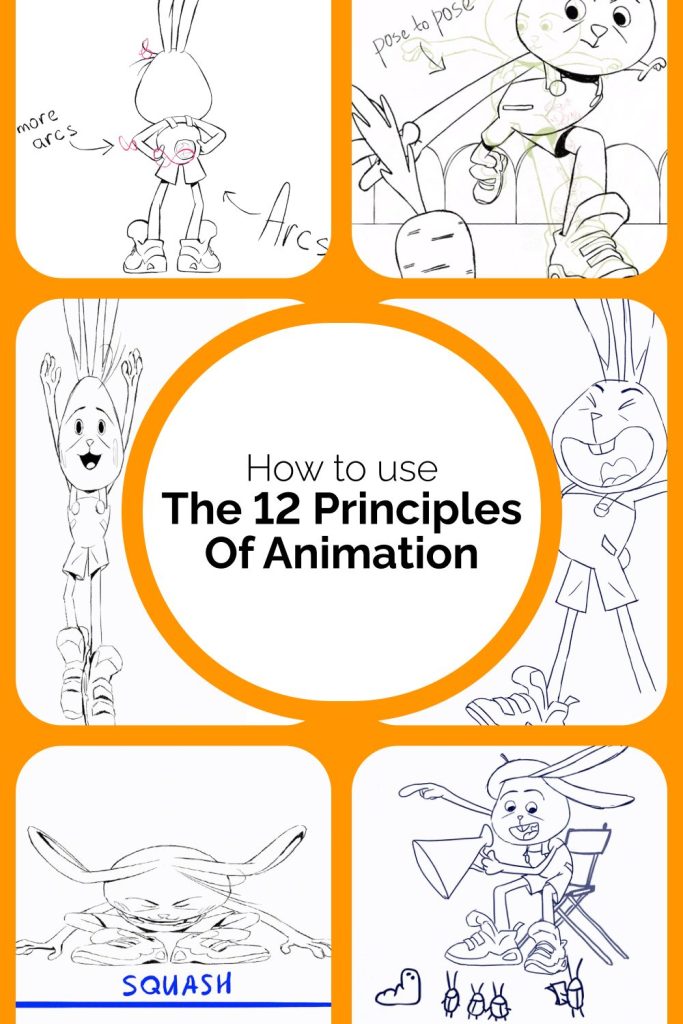

Squash and stretch

A principle that allows you to show the weight, elasticity, stiffness, and the speed of an object. With its help, the animator creates the illusion of flexibility and volume of the character, making the animation comfortable to watch.

Squash and stretch are used to create vivid facial expressions and enhance the pose of a character. But you always have to retain the characters volume, when it. Sometimes special requirements from an animation style will determine how strong you will apply the principle.

Anticipation

Anticipation is the opposite movement before the main action. The more powerful and expressive the main movement, the more pronounced the preparation for it. For example, in order for a spring to shoot, it needs to shrink and gain energy.

Also, the anticipation can be subtle, such as breathing in before a big exhale, or when transferring weight from foot to foot when walking. The animator can show the character’s thought process through anticipation, like the intention to pick up an object through looking at it first, or give a hint about upcoming actions through the character’s delayed gaze off-screen.

Lack of preparation will make the character’s movements abrupt and unexpected, which also can be applied in specific animation.

Staging

Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas have described this principle as “the absolutely clear and unmistakable presentation of thought”.

Staging directs and holds the viewer’s attention to the story unfolding in the frame. It encapsulates acting, directing, timing, camera planing and positioning, and even world building.

The purpose of the principle is to grab the viewer’s attention and explain why that part of the scene is so important to the further development of events.

Straight ahead and pose to pose

Disney animators have described two approaches to animation – to animate the character sequentially from the first pose to the end of the scene (“straight ahead”) or to set up key frames first, and then add in-between poses (“pose to pose”).

By animating “straight ahead” we get the natural flow of an unrestrained action, like fire, water, or hair blowing in the wind. It is possible to achieve spontaneity of movement, but it is difficult to control it for a long time. Also, you lose the original size and proportions of the object, the focus of the animation and the ability to make edits in the process.

The “pose to pose method”, on the other hand, is clearly planned, with keyframes spaced throughout the scene. The size, volume, and proportions of the character, as well as the actions, are much more controlled. The animator doesn’t have to care about every frame, just the ones that are most important to conveyy the main idea of the animation.

Follow Through and Overlapping Action

Follow Through movement indicates that the body parts of the character will continue to move for some time after the character stops.

Overlapping indicates that body parts can move at different speeds and trajectories relative to each other and the character’s body.

These parts can be inanimate objects, clothing, hair, jewellery on the character or some object that overlaps with another, start moving later than the leading part of the object, or move in the opposite direction to the general momentum.

Slow in and slow out

In order to perform an action, any object needs time to generate energy and gain speed. A character can’t run quickly from a static pose, he needs to accelerate. This is called a “slowing in.”

So too does the ending of the movement. The object needs time to lose energy and stop. A moving car at 100 km/h can’t drop to zero in a second. It needs time and a “slowing out” from a high-speed motion.

Arcs

Arcs are lines of action that emerge through the frames. Any movement is just a rotation moving in an arc, whether it’s the swaying of the hips or swinging of the arms, turning your head, or throwing a ball. Arcs can “break” only when the character or object makes contact with something else. Using this principle gives the animation clarity and believability.

Secondary action

This principle is used to enhance and complement the main action in the scene.

In reality, the character’s body, facial expressions, clothes, hair, cars and birds in the background are all moving simultaneously. Therefore, in order for the animation to look believable, it is necessary to add more details to the main action of the character or object.

Sometimes, secondary actions can distract the viewer’s attention from the main action and draw attention to the details.

Timing

The timing tells you how many frames an action will take. This principle determines the speed of the movement and its duration.

Through time calculation you can show the weight, size and even the character’s mood.

Exaggeration

You can exaggerate some of the character’s movements to make them look more expressive. Exaggeration adds more life and dynamics to the animation. You can exaggerate the scale of the movement, deform body parts or objects, as well as distort the perspective.

The main idea is to stay faithful to reality, but present it in a much more wild, extreme form.

Solid drawing/Solid posing

In order to get recognizable movement, you need a well-thought-out drawing and a distinctive silhouette. The principle involves using clear shapes, correctly distributed weight and a natural center of gravity for the object. The poses must convey the character’s intentions, states, thoughts and desires.

Appeal

Every character must have appeal, whether it is a positive hero, a villain, an animal, or a toy.

Attractiveness should permeate throughout the character’s story, character, behavior, and appearance. Even villains should be charismatic and likeable to the audience. Appealing characters are sympathetic, empathetic, and they are being understood.

There are no unambiguous criteria for having appeal, but it can be achieved by using unusual character shapes and proportions, uncommon facial expressions, unexpected movements, and interesting details.

These 12 principles of animation are the foundation for any animators work. It is important to not just know all of the techniques, but to be able to apply them and even break them to create the desired effect in your work. You can get a strong base, practice the principles and collect your first portfolio on the course “Classical 2D Animation. Basics”.

The animations were created by the teachers of the course “Classical 2D Animation” – Edward Kurchevsky, Milena Leonova, Karina Pogorelova and Ksenia Inozemtseva. The character was created by Andrei Sitari, a teacher of the course “Visual Development”.

The article was prepared by Maria Beskorovainaya and Marat Akhmetshin.