What Lessons Can Be Learned From Disney Classic Character Deign?

No story can exist without its hero. Heroes shape the audience’s connection to the film, eliciting empathy, fear, joy, love, and surprise. Walt Disney often told his employees, “Without a distinct personality, our characters won’t be believable.”

Looking at the designs of contemporary Disney studio characters compared to their classic heroes, many differences can be found, which is normal because changes are inevitable.

Modern viewers are incredibly fortunate to see the results of work that has spanned 96 years, as it allows for an understanding of the evolution of character design in the studio.

How was the image of the classic Disney heroes formed? How did it change? And what influenced these changes? To answer these questions, it’s important to first consider the heart of the studio.

Walt Disney’s Big Dream

Walt Disney was always a dreamer. As a child, he would dress up as characters from his favorite fairy tales and tell fascinating stories to his older brother. In his youth, he developed a great interest in creativity. Walt participated in the creation of the school newspaper as an artist and photographer, attended an art academy in the evenings, sold his comics, and learned newspaper caricature. In his later years, he became interested in classical European art.

These interests of Walt were reflected in his work: the first short films of the studio were made in a caricature style, later Disney films were based on fairy tales, and the new style was inspired by classical European art.

Walt strived to amaze his audience with characters, stories, and the magic of moving drawings: “The trouble with the world is that too many people grow up. I don’t make films primarily for children. I make them for the child in each of us, whether he is six or sixty.” Sergei Eisenstein wrote in his study of Disney’s work: “… It seems that this man… knows all the most intimate strings of human thoughts, images, ideas, feelings… He creates somewhere in the area of the purest and most primary depths. There, — where we are all children of nature. He creates at the level of human perception, not yet shackled by logic, reasonableness, experience. Like butterflies create their flight. Like flowers grow… One of the most amazing things about Disney is “The Submarine Circus.” How pure and clear a soul must be to make it. What depths of untouched nature must be dived into with bubbles and kids, similar to bubbles, to achieve such absolute freedom from all categories, all conventions. To be like children. <…> Disney’s epic is “Return to Paradise”… It is not the absurdity of the collision of a child’s concepts of a quirky person with adult reality… And the sadness of the forever lost: childhood by man…”

Disney was a storyteller: in his cartoons, elephants flew, mice talked and danced, and fairies flew. But despite this, he possessed important character traits that brought him success in his beloved work. He was accustomed to hard work from childhood. He never knew luxury and was fanatically hardworking. According to studio employees, “Walt always knew what he needed” and strove for perfection in his work.

That’s why, not yet twenty, Disney found a job as a short animated advertisement artist. Then, together with his colleague Ub Iwerks and his brother Roy, he founded his studio — the Walt Disney Company.

The Evolution of a Studio

Initially, there was no concept artist or character designer position (in modern understanding) at the studio. It’s important to understand that Disney didn’t invent the art of animation, but he “defined its face” and content: gradually discovering new technologies and restructuring the strong internal work on films.

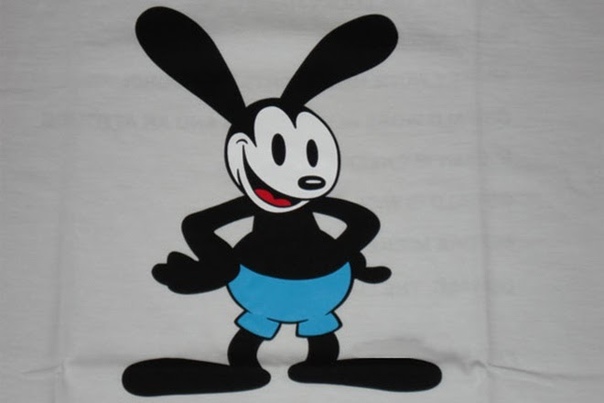

The first independent hero of Disney was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, created by Walt and Ub in 1927. Oswald’s design was tailored for further work: the character was intentionally given long ears and plasticity of forms to expand the character’s capabilities during animation. Thus, in the shorts, Oswald could stretch, flatten, and in the film “Oh, What a Knight!” he twisted into a rope to wring himself dry.

Here Comes Mickey Mouse

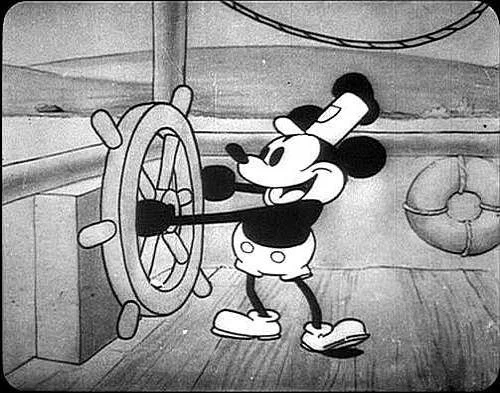

A new character that brought Disney the most fame and popularity was Mickey Mouse. In the early years, Mickey’s design very much resembled Oswald, except for the ears, nose, and tail. The senior animator of the studio, Ub Iwerks, who developed the concept, drew Mickey’s body from circles to simplify the work on animation. Ub Iwerks’ developments largely defined the characteristic style of early Disney animation: rounded, smooth, and caricatured.

Later, studio workers — Marc Davis and John Hench suggested that this design was one of the reasons for Mickey’s success, as it made him more dynamic and attractive to the viewer. In 1938, when Mickey’s fame began to fade in the light of other characters, animator Fred Moore changed his appearance, giving him more flexibility and making his facial expressions more “fashionable.”

Disney’s Biggest Contributions

One of Disney’s most important contributions was the development of the individuality of drawn characters. He wanted viewers to experience a range of emotions and knew that the authenticity of the character was the main element of such success. “After all,” he remarked, “you can’t expect to charm anyone with a moving stick.”

As the business gained momentum, Disney began to pay attention to his most capable employees and directed their energy to work where they could show themselves best. At this time, some artists were assigned to work on character design for animation. Initially, Disney studio animators were responsible for all aspects of the scene: characters, backgrounds, mise-en-scenes, gags, and outlining.

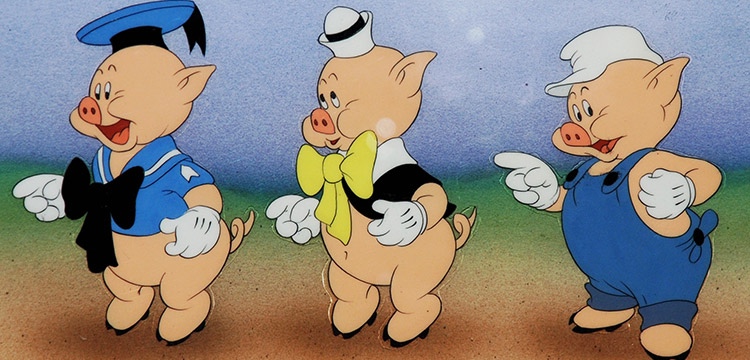

One of these employees was experienced animator Albert Hurter, who worked exclusively on scene sketches for films. His expressive drawings helped develop character personalities, which were then brought to life by other animators. It was Hurter who created the types of the Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf.

Thus, Disney began the specialization in the art of the drawn film.

Want to develop your skills to become Disney Worthy? Join our Mechanics of motion in traditional 2D animation course.

Having exhausted all potential income from short films, in 1934, Disney began working on his first feature film “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

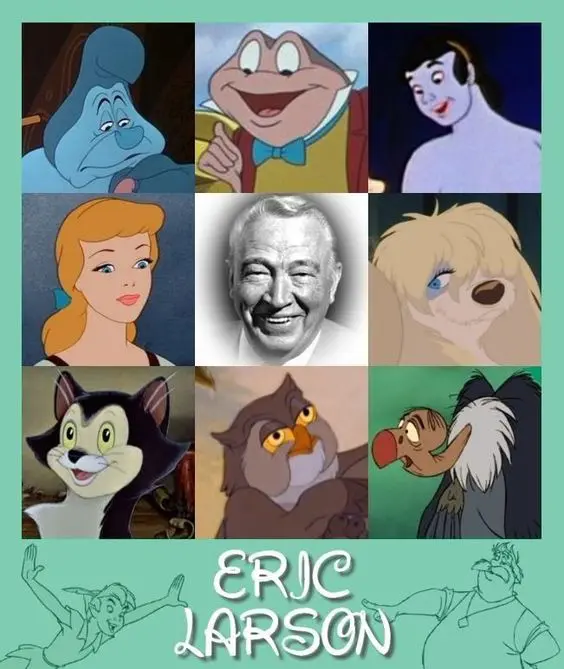

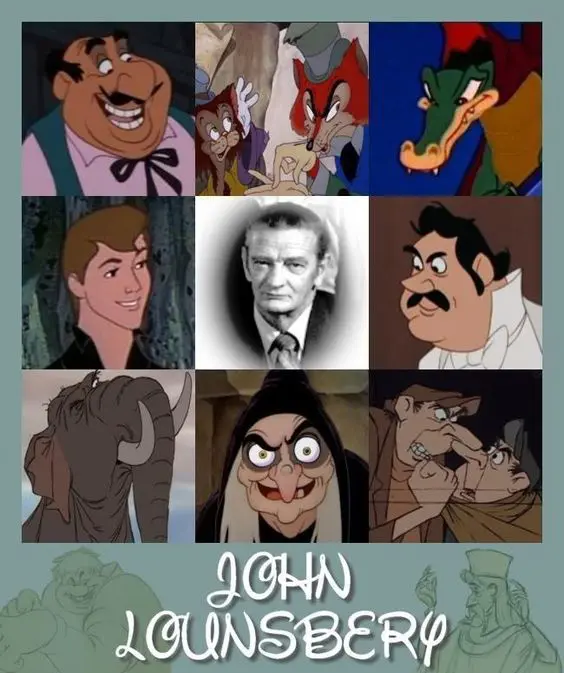

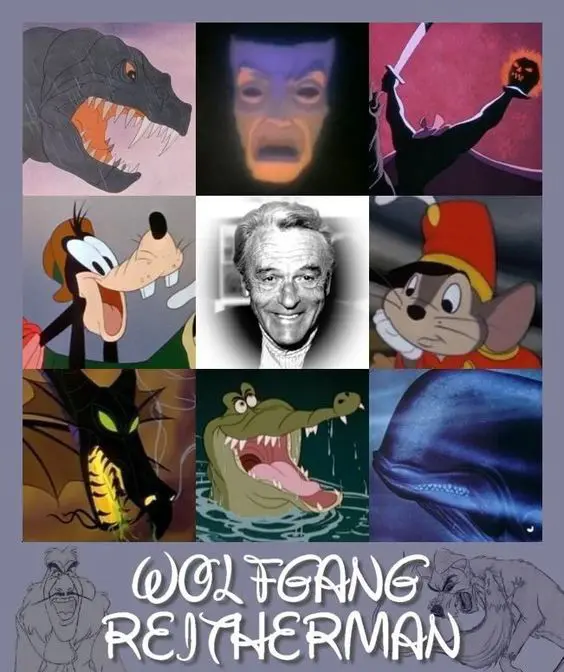

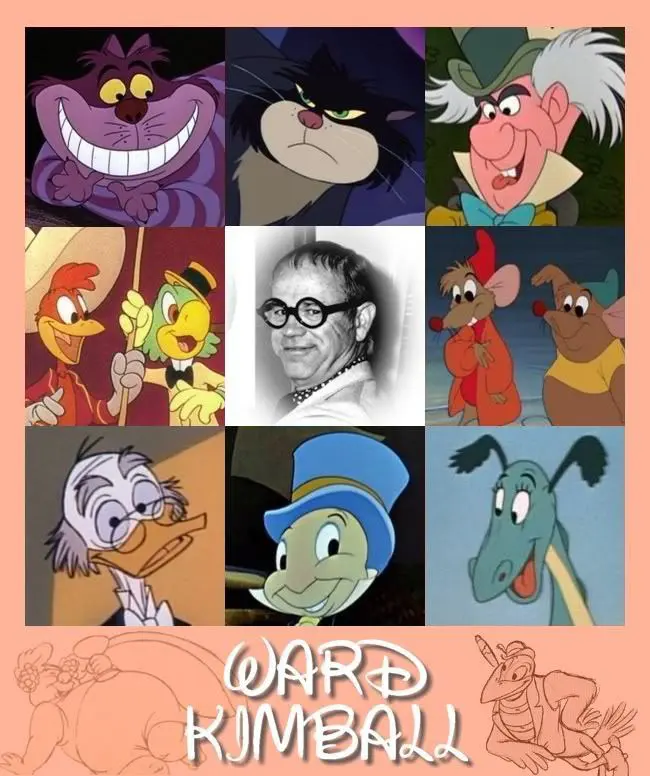

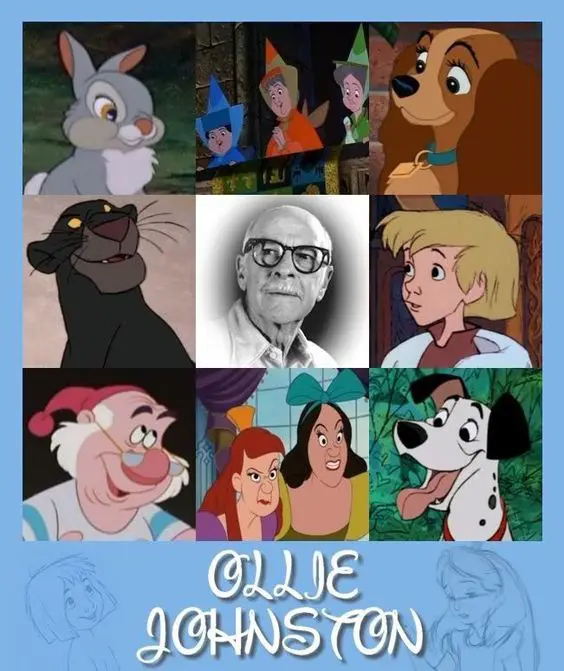

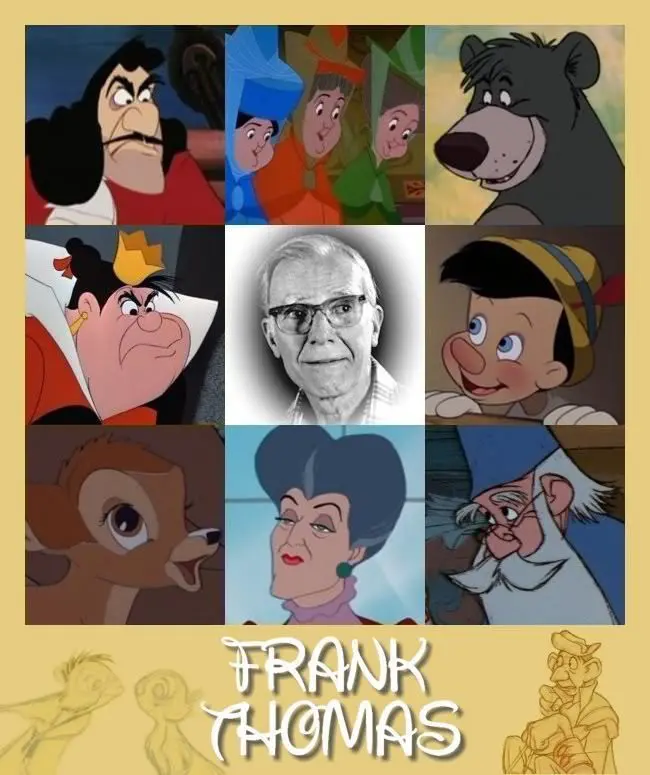

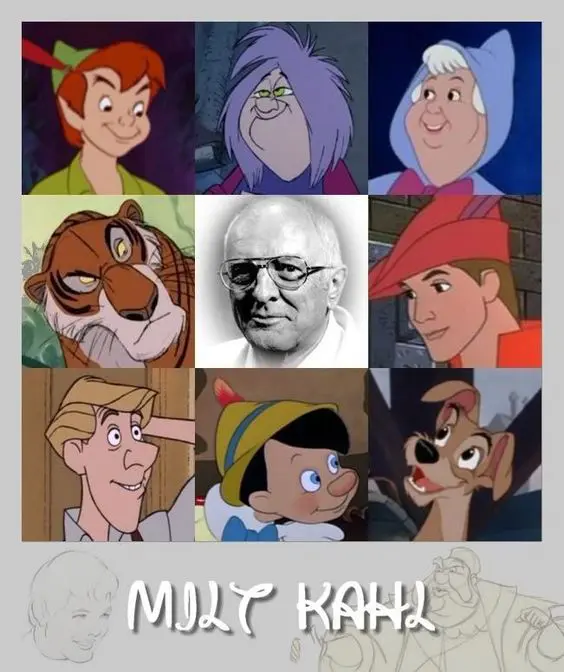

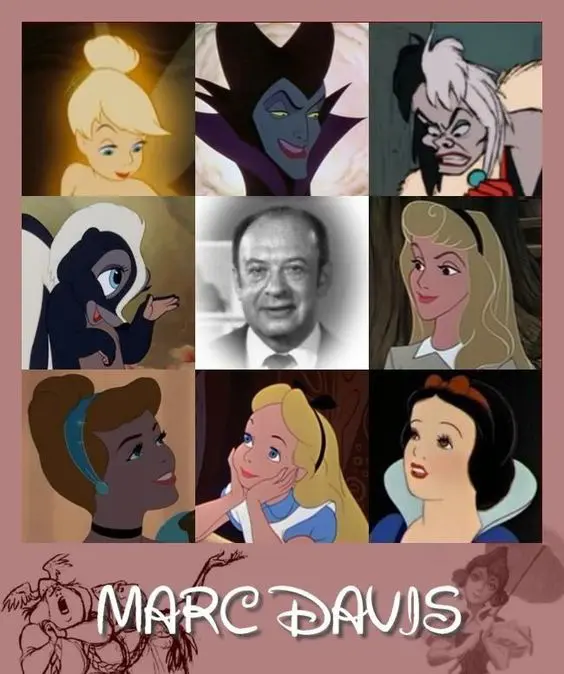

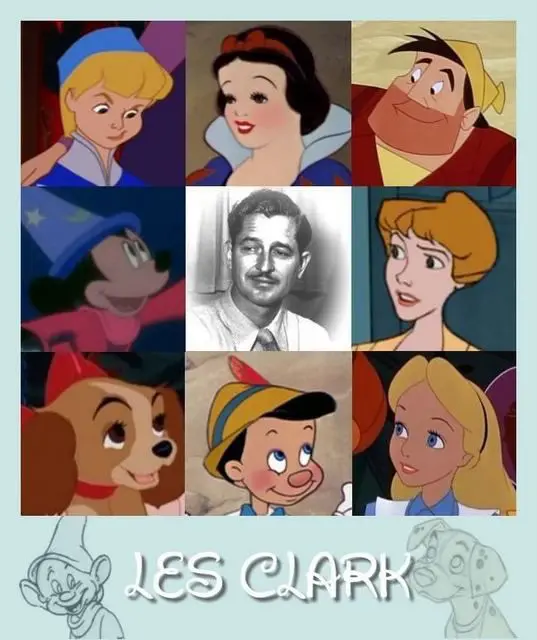

Hundreds of applicants came from all over the country to participate in the big project. Among them were people who later formed the core of Disney’s team — the great “Nine Old Men”: Les Clark, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, Milt Kahl, Marc Davis, Wolfgang (Woolie) Reitherman, Eric Larson, John Lounsbery, and Ward Kimball. This team created a new Disney style: closer to realism, detailed, and rich in color palette.

The legendary “Nine Old Men” of Disney

The most famous works of all from the “Nine Old Men”:

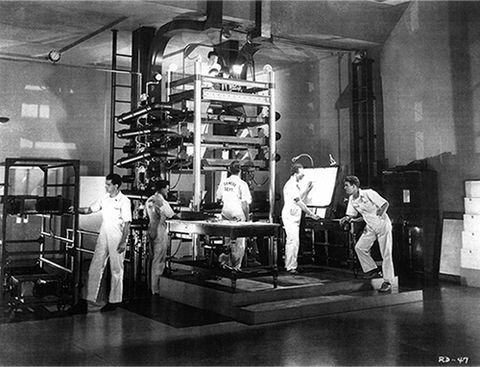

The technologies used at the studio greatly influenced the development of the style.

“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was the result of three years of hard work by 570 artists who, based on precise sketches, created over a million hand-drawn frames every year. Such work required a lot of time, effort, and money.

Disney stated that all scenes with human characters should first be performed by live actors to determine how they would look before starting the expensive animation process. (The estimated budget of the film was $250,000, but by the time filming was completed, the amount was six times more).

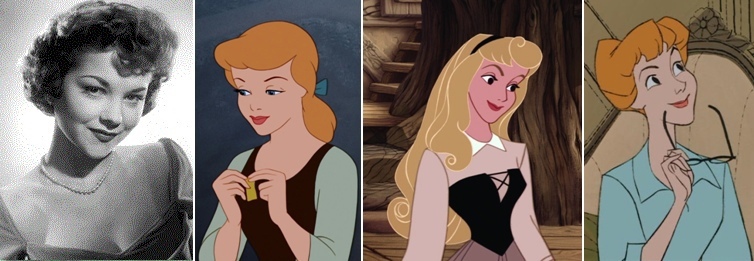

Thus, the rotoscoping technology was used in the studio. For greater realism in movements and character plasticity, live actors were filmed, and then traced. This method became the basis of the realistic and proportional design of characters.

Drawn From Life

Disney wanted the animators “to make the characters in the cartoon as natural as possible, almost in flesh and blood,” but the complexity of developing graphic character design was that previously the animation studio mainly created cartoons about animals and fictional creatures. “Grotesque, exaggeration, and stylization were encouraged, but only to emphasize realism.”

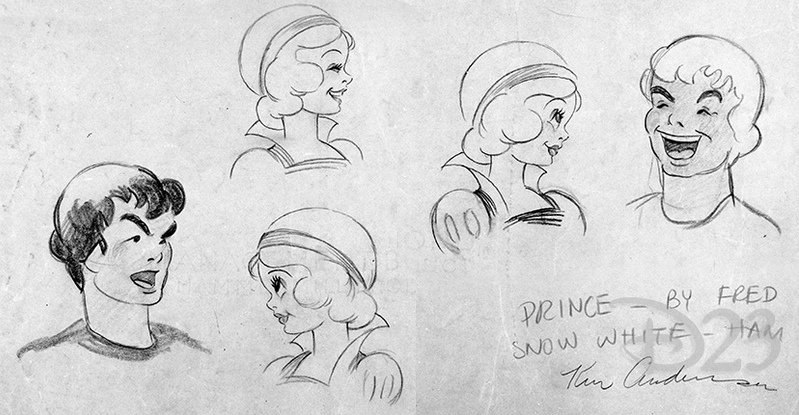

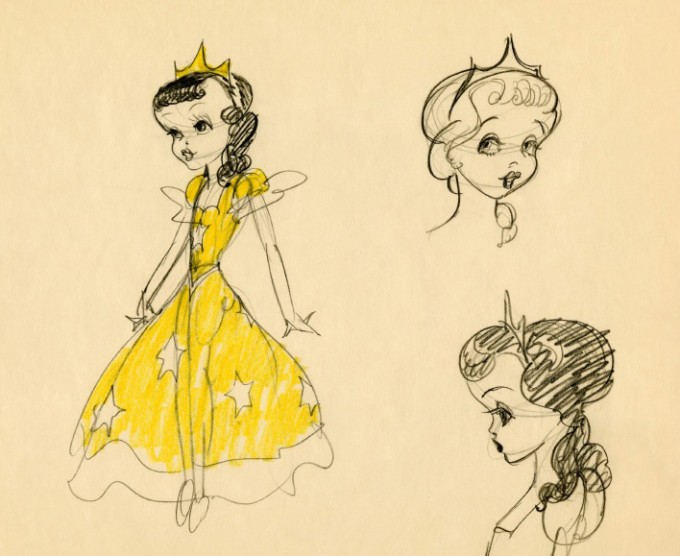

The initial sketches of Snow White, developed by animator Grim Natwick, who previously worked at Fleischer Studios, did not meet Walt Disney’s expectations, as the heroine was very similar to the animated Betty Boop. Also, in some early sketches, Snow White was blonde, which did not correspond to the original fairy tale. Animator Hamilton Luske, at Walt Disney’s request, tried to create a realistic yet fairy-tale and convincing appearance for her, similar to Persephone from the cartoon “Goddess of Spring.” After that, Walt appointed Luske as the lead animator of the film.

To make her movements more plausible, Luske and his team worked with dancer Marjorie Belcher, the daughter of Hollywood dance teacher Ernest Belcher. The girl performed the actions that the artists found most difficult to reproduce “from the head,” without a “reference.” One such scene was Snow White’s dance.

The rotoscoping technology was a significant step in bringing more realistic and natural movements to Disney’s animated characters. Through this process, live actors were filmed performing actions, and then animators traced over the footage frame by frame. This technique was particularly effective in creating believable human characters, which was crucial for the studio’s first feature-length film.

Character Evolution in “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”

The transformation of Snow White’s character design was a complex process. The initial sketches by Grim Natwick, known for creating Betty Boop, didn’t align with Walt Disney’s vision. Natwick’s early designs depicted Snow White as a blonde, which deviated from the character described in the original fairy tale.

To resolve this, animator Hamilton Luske was tasked with redesigning Snow White. Luske’s goal was to blend realistic human proportions with a fairy-tale aesthetic. His final design drew inspiration from Persephone, a character from the 1934 Silly Symphony short “The Goddess of Spring.” Walt Disney appointed Luske as the lead animator for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” ensuring the character met his standards.

To achieve lifelike movements for Snow White, Luske and his team collaborated with dancer Marjorie Belcher, daughter of Hollywood dance instructor Ernest Belcher. Marjorie performed complex actions, such as dancing, which the animators then used as reference material. This method helped bring a natural fluidity to Snow White’s movements, contributing to the film’s groundbreaking realism.

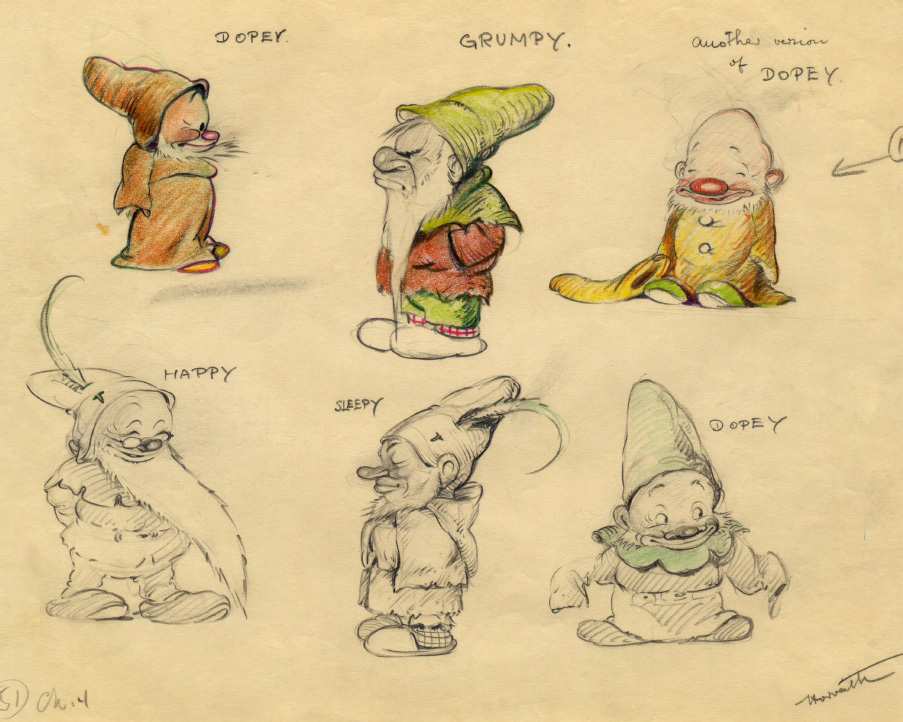

From Sketch to Screen: The Dwarfs

Creating the Seven Dwarfs presented a unique challenge. Each dwarf needed a distinct personality and appearance to stand out. Albert Hurter, a veteran animator, played a crucial role in their development. His expressive drawings helped define the dwarfs’ individual characteristics.

Hurter’s designs were further refined by other animators, who infused the characters with lifelike expressions and movements. This collaborative process resulted in some of the most memorable characters in animation history.

The Influence of Technological Advancements

Technological advancements significantly impacted the evolution of Disney’s character designs. The Multiplane Camera, introduced in 1937, allowed for greater depth and realism in animated scenes. This innovation enabled animators to create more detailed backgrounds and more dynamic character movements.

Disney’s commitment to technological innovation extended to the use of Technicolor, which brought vibrant colors to animated films. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was one of the first films to utilize this technology, resulting in a visually stunning masterpiece.

The Legacy of Classic Disney Characters

The success of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” established a new standard for animation. The film’s characters, with their distinct personalities and realistic movements, set the stage for future Disney classics. The principles developed during this era continue to influence character design in animation today.

The evolution of Disney’s character design reflects a blend of artistic talent, technological innovation, and a commitment to storytelling. From the early caricature styles to the sophisticated designs seen in feature films, Disney characters have captured the hearts of audiences worldwide, cementing their place in animation history.

Thus, character design strives for simplicity, which is more understandable and easy on the eyes and the mind. It’s crucial in character development to strike a balance between easily readable simplicity and the unique personality that the character embodies.

Comparing modern hero design to classic design, it is essential to remember that the “Disney style” did not emerge with the founding of the studio but evolved over a long period. Walt Disney laid the “foundation” of the modern company with his innovations and bold experiments.

Over time, principles were established. Starting with Aurora, the female bodies and faces became increasingly stylized. Then, with the advent of “The Little Mermaid,” the well-known “formula” emerged: “big head, big eyes, small nose and mouth, thin waist,” which was subsequently applied to other Disney characters to varying degrees.

Changes are inevitable, primarily because the factors influencing them change. Techniques change, animators change, studio heads change, the era changes, viewer interests and viewers themselves change, and attitudes change.

Based on the article by Sonia Zhukova edited by Dmitry Shramko